Why the Congregational Church Ought to Recover her Historic Confession of Faith

In the various social groups and organisms of which society is made up of, it is a strong center which breathes life, efficiency, and vitality to any organism. The family is centered upon the covenant or compact which unites two into one flesh. From this center proceeds all vital activity. All the love, concord, and unity of purpose flow from this central point. The force and strength of a family radiates out from this center as beams of light from the sun. A social unit proportionately struggles insofar as its center is weak and ill defined. When the eye of a hurricane is disorganized and undefined, the storm is proportionately weaker. Insofar as a family lacks a due recognition of its binding covenantal underpinnings, it is weaker. There is less amity, peace, and common purpose, and more animosity, discord, and disjointed.

So too is it with Congregational churches. The modern Congregational church must seek to be a united center of activity, at once vital and efficient. One of the means to effectuate this is the revival of a strong confession of faith.[1]

It seems that modern Congregationalists excel more in truncated statements of faith than firm confessions of faith. The statement of faith of the United Church of Christ is brief and uninteresting. More a wax nose moldable to the faith of the hyper-progressive preacher or the docile moderate.[2] That of the National Association of Congregational Christian Churches is a list of “Guiding Principles.” It is more of a list of advertisable slogans than a proclamation of the faith once delivered to the saints.[3] Of the larger bodies of Congregationalists,[4] the best is clearly that of the Conservative Congregational Christian Conference.[5] The Trinity, inerrancy, the exclusivity of Christ, salvation through vicarious satisfaction are all affirmed,[6] and outright Pelagianism is denied. We may thank God there is yet a Congregational lampstand present. May its light not be put out by her Lord.

Even this confession however if weighed in the balance of the genius of Congregationalism is found wanting. Though a true confession, it is a meager confession. It is rather to be lamented that the largest conservative body of Congregationalists adopts a faith with such latitude. Arminianism and Calvinism, Dispensationalism and Covenantalism, Complementarianism and Egalitarianism, Paedobaptism and Credobaptism all darken her doors.[7] The center of Congregationalism is weak. It allows too much latitude and is ill-defined.

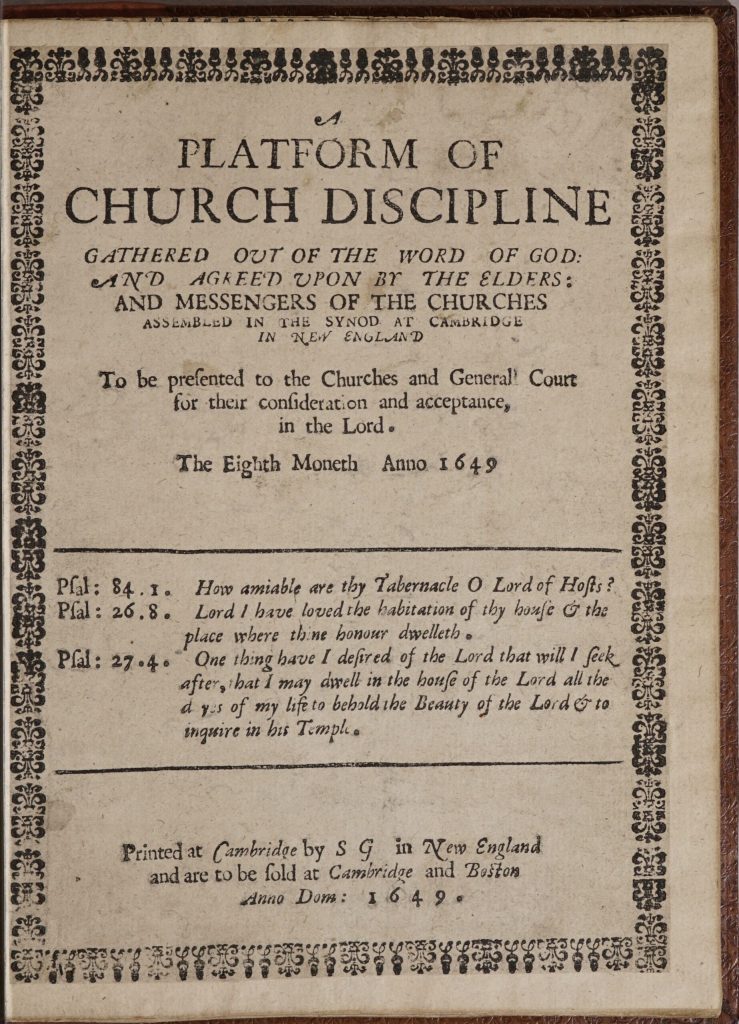

In view of this, we must hearken back to our ancestors. There’s was a faith worthy of emulation. When the New England churches assembled for a synod[8] in 1646 to determine a platform of polity, they determined that a confession of faith was to be determined. Rather than a new confession, they determined that

This synod having perused, and considered (with much gladness of heart, and thankfulness to God) the confession of faith published of late by the reverend assembly in England, do judge it to be very holy, orthodox, and judicious in all matters of faith: and do therefore freely and fully consent thereunto, for the substance thereof.[9]

They adopted “for the substance thereof” the Westminster Confession of Faith. Though separated by polity and church government, they clearly assented to the doctrine of the Westminster Confession such that a newly devised confession was deemed inexpedient in preference thereto. They preferred to adopt the words of the Westminster to stress their agreement with other Reformed churches, and especially those of their native land.[10]

In 1680, another synod in New England considered a confession of faith.

This synod at their second session, which was May 12th, 1680 consulted and considered of a confession of faith. That which was consented unto by the elders and messengers of the Congregational churches in England, who met at the Savoy (being for the most part, some small variations excepted, the same with that which was agreed upon first by the Assembly at Westminster, and was approved of by the Synod at Cambridge in New England, Anno 1648 as also by a general assembly in Scotland) was twice publicly read, examined and approved of: that little variation which we have made from the one, in compliance with the other may be seen by those who please to compare them.[11]

But it was not only Massachusetts that joined in on the confessional festivities. Connecticut too would play its part in the early 18th century.

At a meeting of the delegates from the councils of the several counties of Connecticut Colony in New England in America at Saybrook Sep. 9th, 1708… We agree that the Confession of Faith owned and consented unto by the elders and messengers of the churches assembled at Boston in New England May 12th, 1680 being the second session of that Synod by recommended to the honorable of the General Assembly of this colony at the next session for their public testimony thereto as the faith of the churches of this colony.[12]

Congregationalism’s historic faith has a firm foundation in her church’s historic proceedings. She has always been tethered to a firm and meaty confession. A confession with a firm Protestant conception of Scripture and revelation, a Catholic doctrine of God and Christology, and a Reformed soteriology. A document with fixed notions concerning the obligation of moral and natural law, the Sabbath, worship, and the nature of the church.

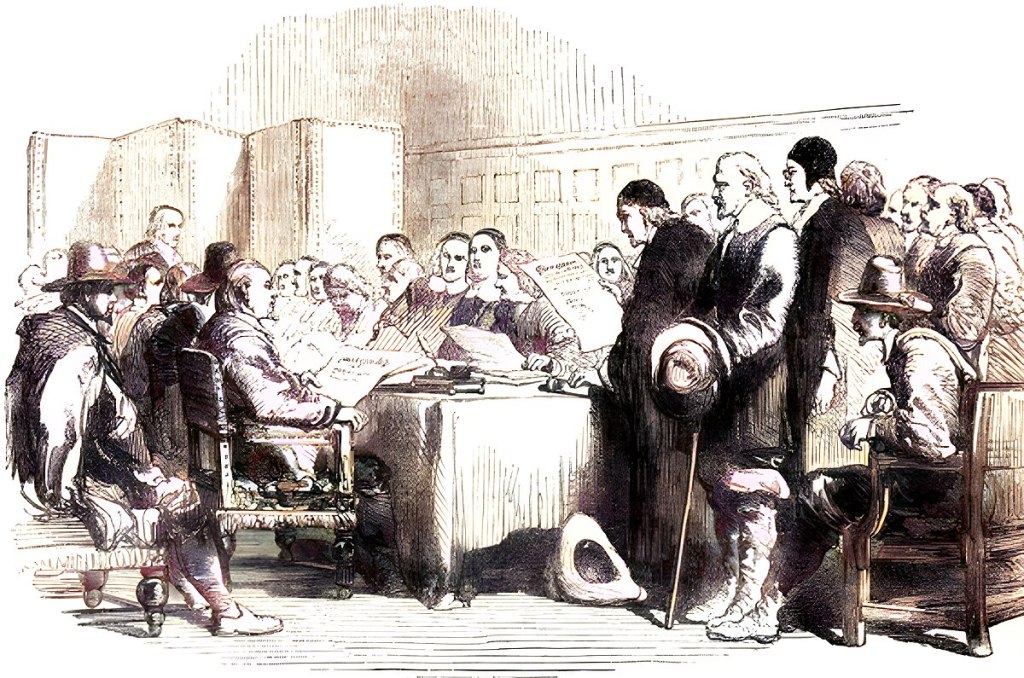

In 1865, a council of the Congregational churches would convene in Boston to affirm her ancestral faith as well.

Standing by the rock where the Pilgrims set foot upon these shores, upon the spot where they worshiped God, and among the graves of the early generations, we, Elders and Messengers of the Congregational churches of the United States in National Council assembled — like them acknowledging no rule of faith but the Word of God — do now declare our adherence to the faith and order of the apostolic and primitive churches held by our fathers, and substantially as embodied in the Confessions and Platforms which our Synods of 1648 and 1680 set forth or reaffirmed. We declare that the experience of the nearly two and a half centuries which have elapsed since the memorable day when, our sires founded here a Christian Commonwealth, with all the development of new forms of error since their times, has only deepened our confidence in the faith and polity of those fathers. We bless God for the inheritance of these doctrines. We invoke the help of the Divine Redeemer, that, through the presence of the promised Comforter, He will enable us to transmit them in purity to our children.[13]

Even in 1865 there is a substantial appreciation of the Savoy/Westminster Confessions. However, the earlier appropriations had been more clear and definite. The 1865 Council’s affirmation of the Savoy was more vague and indefinite.[14] Yet the affirmation is present. Congregationalism in her best days has affirmed her ancestral faith. We would do well to maintain it.

We have the united testimony of three synods and a council and their judgments concerning an appropriate confession of faith ought not be treated lightly by us. We must give preference to the confession historically adopted in our churches. It sustained the piety and promoted the orthodoxy of our ancestors, and it will certainly do the same for us.

The late 19th Century Congregationalist Dorus Clarke concurred with this judgment, affirming that

This system of faith (Calvinism) is the ancestral faith of New England and it must be fully re-established among us, and the thorough piety, which is its natural exponent, must be fully restored, or the power and glory of these churches will depart, and ought to depart.[15]

The following words of William Greenough Thayer Shedd concur together with Clarke’s, and add the consideration that formidable creeds are part of the heritage of Congregationalism.

This brief survey is sufficient to show that those who laid the foundations of Congregationalism, in the Old World and in the New, were in hearty sympathy with that body of doctrine which received its precise and technical statement in the creeds of the Reformation, and more particularly in that carefully discriminated system which was the result of the debate between Calvinism and Arminianism. The carefulness, and the frequency (three times within sixty years) with which symbols were drawn up and sent forth by the first Congregational churches evinces that both the individual theologian, and the denomination as a whole, craved a distinct, and publicly adopted, rule of faith and practice, as that which should help them to study the Scriptures understandingly, and should bind them together ecclesiastically. Reverence for a common denominational creed belongs, then, historically, to the Congregational church, as it does to all those well-compacted churches whose career constitutes the history of vital Christianity upon earth. In seeking to deepen and strengthen this reverence, we are not going contrary to the primal instinct and native genius of Congregationalism; we are not engrafting any wild shoots into the church of our forefathers; we are simply inhaling and exhaling their pure, their exact, their thorough-going spirit.[16]

Only by returning to her historic confession can Congregational churches achieve strong and vital churches. Bodies which can whether the storms of post-modern insanity, be tethered to the natural and supernatural orders, and be a faithful witness for the truths of revelation. As modern Congregationalism recovers her sense of identity and makes the Savoy Delcaration her own faith, we can be assured that her energy will increase tenfold. Unity and mutual love will be strengthened, and a common end more effectually pursued. Hard times demand meat rather than milk.

[1] For an expanded treatment upon this topic, see Symbols and Congregationalism, W.G.T. Shedd.

[2] https://www.ucc.org/what-we-believe/worship/statement-of-faith/

[3] https://www.naccc.org/about-us/about-congregationalism/

[4] This judgment is made of American bodies. I’ll allow our British cousins to adjudicate which is best across the pond at present.

[5] https://www.ccccusa.com/about-us/statement-of-faith/

[6] Among the other fundamental doctrines.

[7] Not to speak of the more niche yet important theological issues that were dealt with in the historic Confession.

[8] Council, conference, or assembly would probably be the modern jargon most closely approximate.

[9] Walker, Willison, Creeds and Platforms of Congregationalism, 195.

[10] “Now by this our professed consent and free concurrence with them in all the doctrinals of religion, we hope, it may appear to the world, that as we are a remnant of the people of the same nation with them: so we are professors of the same common faith, and fellow heirs of the same common salvation.” Walker, Creeds and Platforms, 195.

[11] Walker, Creeds and Platforms, 439.

[12] Walker, Creeds and Platforms, 518.

[13] Yerrinton, J.M.W, Parkhurst, Henry M., Debates and Proceedings of the National Council of Congregational Churches, 361.

[14] The Council of 1865 warrants more study by Congregationalists. Whereas on one hand it affirmed the Savoy Declaration of Faith, with another it opened up Congregational churches to a broader latitude of doctrine that undoubtedly had some degree of influence in bringing us to the present doctrinal situation of Congregational churches.

[15] Clarke, Dorus, Orthodox Congregationalism, 138.

[16] Shedd, William G.T., Theological Essays, 327-328.