The strictness of the New England Sabbath is proverbial, and has only its equal in the Scotch Sabbath. Its strict observance was an essential part of that moral discipline which made New England what it is today, and is abundantly justified by its fruits, which are felt more and more throughout the whole Christian world.[1]

Let us never forget the debt of gratitude which we owe to New England for the strict observance of the Sabbath.[2]

If there is any way in which the modern Congregational church has fallen from her heritage, it is in observance of the Lord’s Day, otherwise formerly referred to as the Christian Sabbath. It seems as though what has been called the “Continental Sabbath” has won the hearts of the progeny of some the Sabbath’s most devoted observers. The modern Congregational is now no different from the resident Lutherans and Catholics among which they reside, which in many cases is not all that different from the lukewarm religionist, whose only rule in Sabbath observance is to go to church when one sees fit.

Most attenders upon Congregational churches see the Sabbath, if they even admit the abiding validity of the 4th Commandment, as fulfilled during the hour-long church service. It is now no longer one day in seven, but one hour in 24. The symptoms of this change are evident. One would be hard-pressed to find a Congregational church that has a morning and evening service. Our conversation (both verbally and bodily) savors more of our concerns than the Lord’s concerns. Rather than duly meditating upon God and his benefits in Christ, we meditate upon Sunday football and how to make others work for us in restaurants. All is not well in this predicament.

Our fathers were no doubt holier and more intelligent than we are. To have cast off such a rich inheritance as is the Lord’s Day is both palpably evil and absurd. We want the spiritual benefits of a past era but neglect the means to them. You cannot have your cake and eat it too. In order to imitate the holiness of our fathers and partake of the rich spiritual blessings that they observed, there must be a recovery of a robust Sabbath. Not merely what passes under the name of a “Continental Sabbath,” but what Philip Schaff has called “The Anglo-American Sabbath.”[3]

What brings him to our attention however is an essay he presented before the National Sabbath Convention in Saratoga, NY on August 11th, 1863. In this work, Schaff presents a basic theological presentation of what he calls the “Anglo-American Sabbath” together with its blessings and superiority to the “Continental Sabbath.”[4]

As the quotes above indicate, Schaff sees the Sabbath as practiced particularly in Scotland and New England as immeasurably superior to the Sabbath as practiced in his own native lands of Germany, Switzerland, etc. Not only is this evident in the supernatural benefits those countries enjoy, but also in the natural benefits. Quite literally, Schaff thinks the relative virtue, freedom, wealth, and political greatness. I don’t think he’s wrong either.

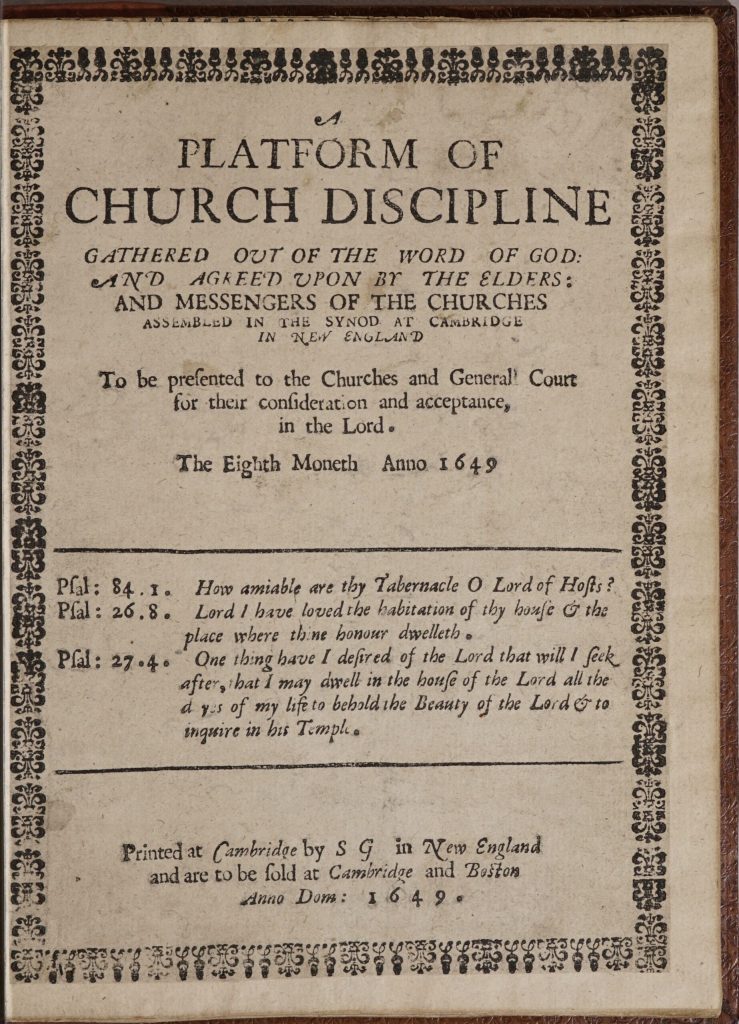

As he notes, New England would become known from the 17th-19th centuries as a strict promoter of the Lord’s Day. This institution would become an American institution as well, as the historic state constitutional laws prove. The temporal and eternal good of individuals and societies is in many ways predicated on how well they observe Sabbath. Our Congregational forefathers in New England promoted a thick doctrine and practice of the Sabbath, and we have lost out insofar as we have failed to live up to it.

Lest we think that the Sabbath is merely a ceremonial or arbitrary commandment with no particular weight attached to it, let us listen to some of our forefathers.

Thomas Shepard would state that “religion is just as the Sabbath is, and decays and grows as the Sabbath is esteemed: the immediate honor and worship of God, which is brought forth and swaddled in the three first commandments, is nursed up and suckled in the bosom of the Sabbath.”[5]

Benjamin Colman would proclaim that “it is visible that the decay of sanctity bears proportion to our declension in Sabbath sanctification.”[6]

Quotes to this effect could be quoted ad nauseam. The vitality and strength of religion is proportionately related to how well the Sabbath is observed, kept, and maintained. If the latter is strong, then the former is strong. If the latter is weak, then so is the former.

Even in the later 19th Century, Henry Martyn Dexter would speak of the Sabbath and its importance in striking terms.

This much, at least, seems to be clear: that the Congregational churches of the United States stand pledged before the world by their own voluntary declarations, four times with solemn publicity repeated within fifteen years to the commonly called Evangelical, in distinction from the unevangelical doctrines. So that it may earnestly be doubted whether any church, or any minister who — taking the ground that Congregational ism is a mere form of polity which may coexist with any dogmatic conviction — claims to remain in good and regular Congregational standing while believing and teaching loose views of Inspiration; denying the sanctity of the Sabbath; the divinity of Jesus; man’s need of an atonement, and that need met in the death of Christ; the salvation of the penitent redeemed by grace, and the everlasting punishment of the impenitent wicked.[7]

Dexter positively classes the sanctity of the Sabbath together with the divinity of Jesus and atonement in the death of Christ. We may question the exact relation of the Sabbath to these fundamental doctrines without the belief of which there is no salvation, but it should be evident the Sabbath is no small thing. It is no small addendum to religion, but a significant sign of a people’s profession of the Christian faith.

This being the case, this blog will in the future interact with Thomas Shepard’s Theses Sabbaticae in the hope that engagement with the historic Congregational doctrine and practice of the Sabbath stirs existing Congregational churches to take up her historic doctrine and practice in this regard. May we all come to truly call the Sabbath a delight.

[1] Schaff, The Anglo-American Sabbath, p. 57.

[2] Ibid, 62.

[3] Philip Schaff was a bit of an enigmatic figure. A Swiss-born theologian who studied in Germany at world class universities such as Tubingen, Halle, and Berlin. He would migrate to America, and together with John Williamson Nevin become leader of a movement known as the Mercersburg Theology. He would teach for a time at the German Reformed Theological Seminary in Mercersburg, PA but would terminate his career at the more nationally renown Union Seminary in New York City. His prodigious learning is evident to anyone who glances at his eight volume History of the Christian Church. Truly a man of immense learning and indomitable scholarly zeal.

[4] By saying this I’m not entering into the fray of how and insofar the British and Continental Reformed agreed and/or differed with regards to the Sabbath. I use these terms merely as helpful descriptors of two different theologies and practices regarding the Christian Sabbath. Suffice it to say the historic practice of the Continental Reformed had much similarity with the British Reformed and would probably shock many modern self-professed promoters of the “Continental Sabbath.”

[5] Shepard, Theses Sabbaticae, p. 13.

[6] Colman, The Doctrine and Law of the Sabbath, p. 1-2.

[7] Dexter, Hand-Book of Congregationalism, p. 79-80.