Doctrine is the lifeblood of a sound Christian profession. After all, is it meaningful to consider somebody a Christian who denies the existence of God, the possibility of miracles, the vicarious death of Christ for sinners, or his bodily resurrection? Would we link arms and maintain Christian fellowship with somebody who maintains that Christ was merely a human teacher, and taught us that we can be justified before God on account of our own works or merits? No doubt the catechized Christian recoils in horror from such a thought. It is evident that doctrine, or agreed upon beliefs grounded upon a supernatural authority, constitutes the terms for Christian communion and fellowship. In order to be considered a Christian, one must assent to such doctrine, believe it with their heart, and confess it with their lips.

Clearly somebody who denies that God exists or that Jesus was not raised from the dead is not worthy of being seriously entertained as a Christian. Beyond these basic or fundamental claims, what do we make of a professing Christian who disagrees with us about who ought to be baptized? What about a fellow believer who believes in a different church polity? How do we relate with a saint by profession who has a different view of the end times? No doubt, most Christians recognize that though doctrine is important, there is some latitude in doctrine such that, though we disagree with a fellow believer said doctrine, we would not doubt that they are a genuine Christian, united to the same Christ, and participant in the same Spirit.

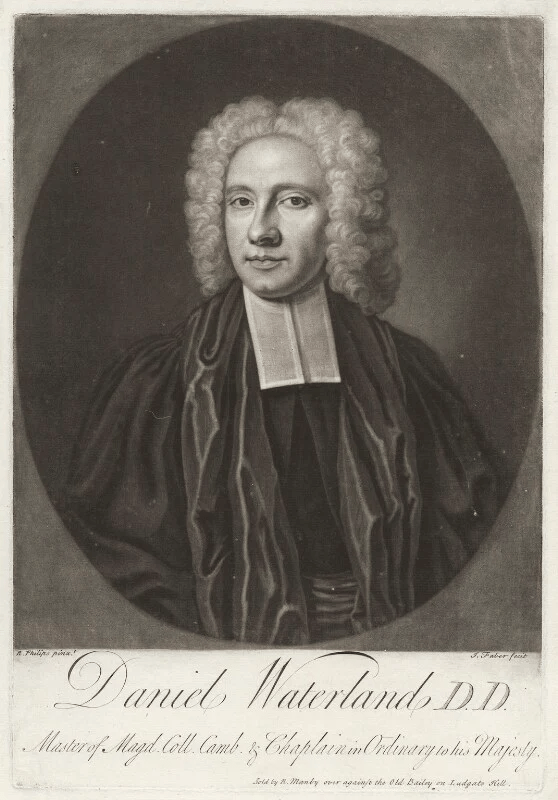

What we are gesturing toward is a distinction between fundamental and non-fundamental doctrine. Not all doctrines are the same, and there are different degrees of importance among doctrines. For something to be fundamental, Noah Webster helps us by defining fundamental as “Pertaining to the foundation or basis; serving for the foundation. Hence, essential; important; as a fundamental truth or principle; a fundamental law; a fundamental sound or chord in music.”[1] Some doctrines serve as the foundation or basis without which a pretension to saving faith in Christ cannot stand. Like a building which lacks a foundation and so comes crashing down, a faith without fundamental doctrines is a faith fatally defective. The 18th Century Anglican theologian Daniel Waterland would note concerning fundamental doctrines, they are “something essential to religion or Christianity; so necessary to its being, or at least to its well-being, that it could not subsist, or not maintain itself tolerably without it.”[2] Joining the voice of Waterland is Francis Turretin who would say that they are the “essential doctrines of Christianity of which the theory and practice is necessary simply as to the thing itself; or which are simply and absolutely necessary to be believed by all Christians and cannot be unknown or denied without peril to salvation.”[3] To this can be further added the definition of Herman Witsius, who said that “A doctrine, without the knowledge and faith of which, God does not save grown-up persons, is necessary to salvation.”[4]

In proof of this point, Scripture points us to some distinction among truths and doctrines to be assented to. Jesus could speak of “weightier matters of the law.”[5] He further commands Christians not to fight over opinions and commands the church to receive those weaker in faith; Rom. 14. He even gives a certain prioritization of the gospel to baptism, when he stated that “Christ did not send me to baptize but to preach the gospel.”[6] In further defense of this distinction, Daniel Waterland notes as follows,

There were in the days of the Apostles, Judaizers of two several kinds; some thinking themselves obliged, as Jews, to retain their Judaism along with Christianity, others conceiving that the Mosaical Law was so necessary, that it ought to be received, under pain of damnation, by all whether Jews, or Gentiles. Both the opinions were wrong; but the one was tolerable, and other was intolerable. Wherefore St. Paul complied in some measure with the Judaizers of the first sort, being willing, in such cases, to become all things to all men: And he exhorted his new converts of the Gentiles, to bear with them, and to receive them as brethren. But as to the Judaizers of the second sort, he would not give place to them by subjection, no not for an hour, lest the truth of the gospel should fatally suffer by it. He anathematized them as subverters of the faith of Christ, and as a reproach to the Christian name.[7]

If fundamental doctrine is essential doctrine, non-fundamental doctrine is clearly not essential. True Christian faith can exist where non-fundamental doctrines are denied or not maintained. Though wood, hay or stubble be built thereon, the foundation stands firm. This is not to say, however, that non-fundamental doctrines are unimportant. As Gavin Ortlund notes, nonessential doctrines are significant to Scripture, significant to church history, significant to the Christian life, and significant to essential doctrine.[8] Though not essential to salvation, or the esse of a Christian profession, they are certainly necessary to the bene esse or well-beingof a Christian profession. Not only so, but they are doctrines supernaturally revealed by God and thus we are obligated to receive them as well, such that it is sin to deny or neglect them.

It is easy to acknowledge the distinction between fundamentals and non-fundamentals, it is harder to enumerate a list of fundamental doctrines. Numerous theologians given various rules for aiding in determining whether a doctrine is fundamental or not. What should be kept in mind is that we are using doctrine in a broader sense, so as to include matters of faith, worship, and morality. All of these constitute the fundamental doctrines of the Christian faith. Additionally, we must distinguish between fundamentals absolutely and fundamentals in relation to particular persons, and note that in the following discussion we are concerned with the former. This last point is on account of the different capacities of men’s minds to receive the truth. Some are more intellectually gifted than others, and so are able to receive and express the truth with more clarity. Not only that, but most Christians agree that infants and mentally handicapped people may be saved, yet the degree of their apprehension of doctrine runs anywhere from minimal to none. We are more concerned with determining what are the absolute fundamental doctrines without which a true Christian system of faith can subsist. In the next post, we’ll enumerate Waterland’s taxonymy and answer objections.

[1] Webster, 1828 American Dictionary of the English Language.

[2] Waterland, A Discourse of Fundamentals, 4.

[3] Turretin, Institutes of Elenctic Theology, 49.

[4] Witsius, Sacred Dissertations, 16-17.

[5] Matt. 23:23

[6] 1 Cor. 1:17

[7] Waterland, A Discourse of Fundamentals, 5-6.

[8] Ortlund, Theological Triage, 43-52.