Lest the precious candle light of our forefathers’ faith be forgotten, the dead must be made to speak. To secure this end, I will begin a series where I introduce historic Congregational essays and books long forgotten that promoted Orthodox Congregationalism, both in doctrine and practice; faith and observance. Enjoy

Thomas Clap (June 26, 1703 – January 7, 1767) was the 5th Rector and 1st President of Yale College from 1740-1766. His tenure at Yale was an embattled one. Spars and combat seemed to define his presidency. Whether it was with Old Lights, New Lights, or Episcopalians, he had his share of trials. Such is why the “Puritan Protaganist” was known as rigid, authoritarian, dogmatic, and obstinate. Such is why we should like him.

He introduced various educational reforms at Yale, but the reputation handed down to us is formed by his effort to maintain good, old Puritan doctrine and ethos at Yale.

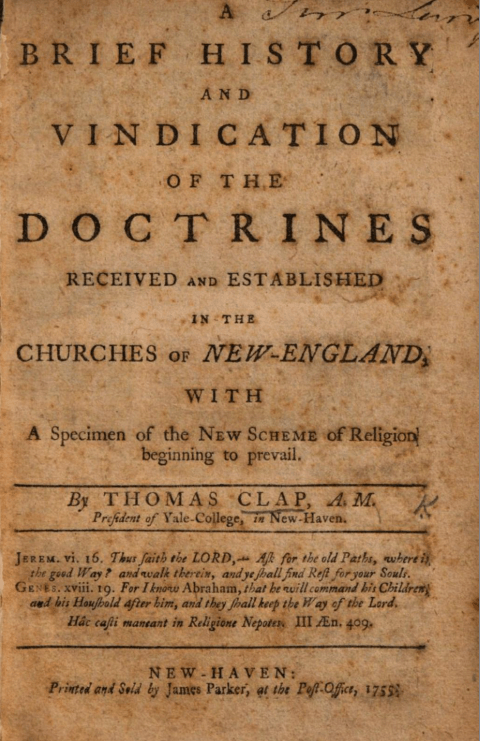

In 1755, he authored A Brief History and Vindication of the Doctrines Received and Established in the Churches of New England. Therein, Thomas Clap vindicates the common faith of the New England churches as confessed in her Confession–the Savoy as amended at Boston in 1680–and Catechism; the Westminster Shorter Catechism.

“Religion is a matter of the greatest consequence and importance, as it respects our highest duty and happiness.” In light of this cardinal principle, the first planters of New England went on their errand to “enjoy religion in the purity of its doctrines, discipline, and worship, and transmit the same down to the latest posterity.”

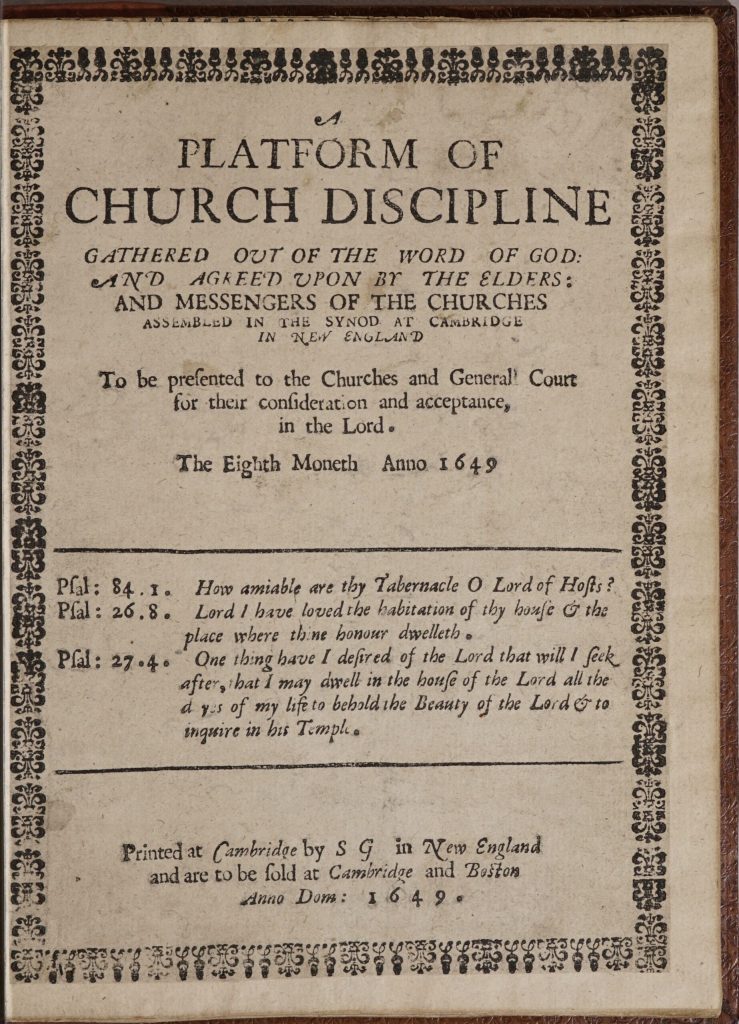

The faith they professed was that generally established in all ages of the Christian church and declared in the various confessions of the Protestant churches. The Cambridge Synod of 1648, Boston Synod of 1680, and Saybrook Synod of 1708 all (in their varying manners) adopted either the Westminster Confession of Faith or Savoy Declaration.

To propogate this faith, schools were erected and the ministry trained up in the liberal arts and religious principles so that this Christian faith could be handed down to posterity. After this ground work, Clap brings the discussion to the charter of Yale College and various acts of the trustees and fellows. The school was founded to “propogate in this wilderness the blessed reformed Protestant religion.” This is confirmed by sundry acts whereby strict subscription is expected of the rector and tutors of the school to the Confession of Faith adopted at Saybrook. Not only so, but the trustees are empowered to examine and prosecute any rector or tutor suspected to not be in line with the Confession and Catechism, and especially those thought to be indulging in “Arminian or Prelatic principles.”

Having enumerate these acts, he introduces and defines a “new scheme of religion” threatening the college and its students, presumably in light of religious changes across the sea and the Enlightenment. This “scheme” is largely one that downplays the importance of speculative doctrine in favor of practical morality. Its grand error is making human happiness itself the chief end of human existence and action, and its practical effect is to reduce the Christian religion to merely living in accordance with the light of nature.

Having listed the promoters of this scheme, he notes the chief way whereby they prepare unsuspecting fellows to receive their poison. This is by denigrating creeds and confessions.

It is at this juncture that Thomas Clap defends the utility of creeds as testimonies and tests of faith together with the idea of Christianity as having certain fundamental doctrines. Every person, and by extension every public body (i.e. church) has a right to judge for itself in propositions its sense of the meaning of Word of God and to expect their officers and public teachers to be conformed to that standard. Furthermore, to deny fundamental doctrines to Christianity is tantamount to saying it has no essence and existence. For something to have an essence, it must have a foundation.

Additionally, he defends chief doctrines such as the Trinity, original sin, and generic Augustinianism from the historic councils of the church, thus showing that these doctrines are no invention of a zealous sect, but rather that they are the common deposit of that great mass of pious Christians throughout history, and thus New England’s historic faith is vindicated.

He terminates his essay with several timely practical reflections. We cannot let candidates for the ministry (though by extension any religious teacher) assume their functions by affirming the substance of a creed. Rather they must be expected (atleast) to enumerate their exceptions to the creed and leave it in the determining body to determine whether they will still accept them. He warns however that giving up any doctrine is difficult if not dangerous as their is a harmonious relation between all doctrines. As soon as one domino falls, the others must follow. There is a blessed inconsistency in many men’s doctrinal notions, but nonetheless we ought be very cautious in so allowing doctrinal exceptions.

Sometimes men will assent to a confession, yet make mental equivocations from the commonly received interpretation of a confession. They retain a different sense of the words, and so implicitly we must be on the watch for such equivocators.

As Christians, we are called to put on the virtues of condescension and charity, but that doesn’t give license to look over doctrinal abberations. Rather, any lasting unity is founded in a joint confession of the fundamental principles of religion. Only then can be united as our Lord thus prayed in His High Priestly Prayer.