But we have (for the main) chosen to express ourselves in the words of those Reverend Assemblies (Westminster and Savoy), that so we might not only with one heart, but with one mouth glorify God, and our Lord Jesus Christ. – Preface to the Confession of Faith… of the churches assembled at Boston in New England, May 12th, 1680.

In order to salvation, in order to receive the paternal “Well done good and faithful servant,” St. Paul notes that confession of the lips in addition to belief of the heart is necessary. Words as external signs expressive of one’s internal knowledge and assent are necessary (ordinarily) to be saved. Such is why our Lord proclaimed with dogmatic utterance that “whoever confesses me before men, him I will also confess before my Father who is in heaven.”[1] Such is why St. Paul told Timothy to “Hold fast the form of sound words, which thou has heard of me, in faith and love which is in Christ Jesus.”[2] Words matter. Not merely ideas and propositions internally assented to, but ideas and propositions externally expressed. Religion of the heart as well as of the mouth.

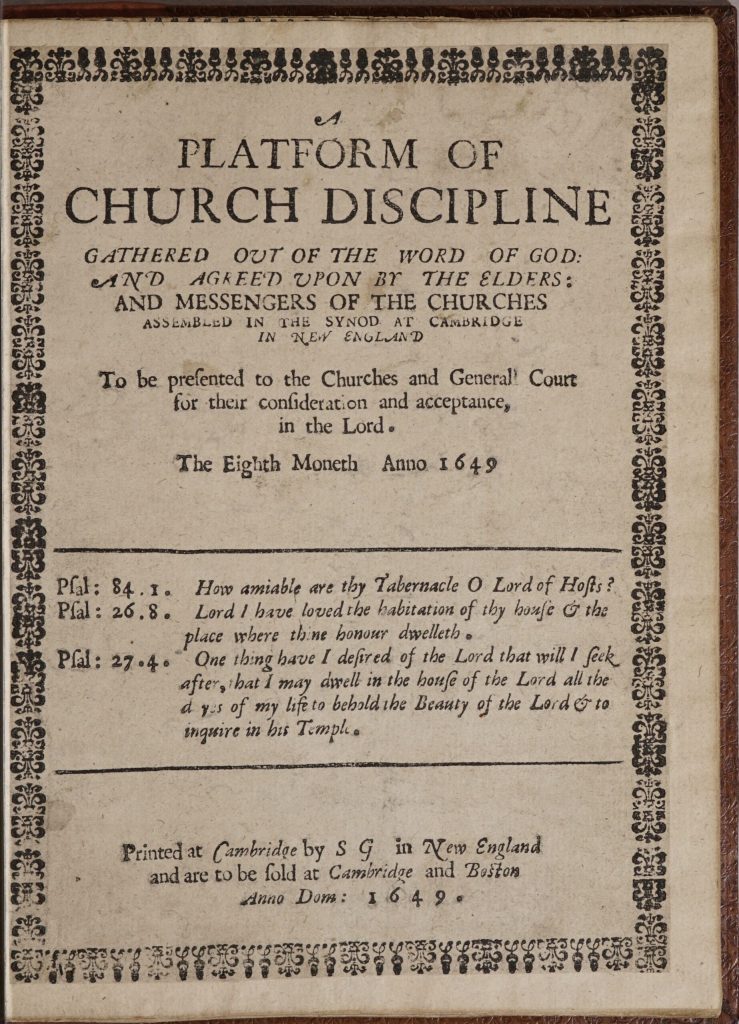

Because words are important, we should be slow to sell our historic patrimony of theological language bequeathed to us in our symbols, creeds, and theological literature. As Reformed Congregationalists, we should be slow to sell the “form of sounds words” taught us by the Savoy Declaration, Cambridge Platform, and authors such as John Owen, Thomas Goodwin, John Cotton, Samuel Willard among others.

Hitting upon this theme, Leonard Woods, professor of systematic theology at Andover Seminary in the 19th century, enumerated the deleterious effects of appropriating new theological terminology and abandoning the old.

An attempt to exclude those words or phrases from common use, and to introduce new modes of expression in their stead, generally leads to evil consequences. It is apt to occasion mistake and confusion in the minds of Christians, who will be very likely to think that the new phraseology implies a new doctrine, and a rejection of the old.[3]

In fact this adoption of new phraseology causes bitterness and strife between the old and the new guard, and as Woods notes, “the strife is little more than logomachy.” Both useless quarrelling and imputations of heterodoxy (if not worse) are the natural fruit of adopting a new theological vocabulary.

But doesn’t the common phraseology admit of misunderstanding and abuse? Hasn’t justification by faith alone brought in its train antinomian licentiousness? Hasn’t predestination fostered the most degrading fatalism? Hasn’t the Trinity made men to conceive of God as a three-headed Cerberus? Musn’t we reject misunderstood phraseology and find greener grass? As Dr. Woods proclaimed; “Certainly not.”

Rather than trading the old language, “Christian candor and charity” demand that we “take pains to guard the language in common use against misconstruction, and, so far as justice will admit, to give it an explanation in accordance with the truth, — to give it the best sense it will bear; — it being generally the case that this favorable sense is the sense which was intended by those who first employed the language, and which naturally occurs to all well-instructed and unprejudiced persons.”[4]

“Our duty is to explain the language which is used to express it, — and to point out clearly the errors which lie in its neighborhood, and which are to be avoided.”[5] We must honor our patrimony and the sacred obligation of truth by maintaining a manly, dogged, and tenacious hold upon that language which sacred custom, the consent of ages, has given to our confessional and theological heritage. Should error be imputed to it, we must explain the language in its honest, orthodox, and biblical sense. We must ever produce expositions and statements of the natural and orthodox sense in which our confessions, catechisms, and theological authors are to be taken.

Evil must ensue upon the adoption of a new and foreign theological vocabulary. Confusion is in its wake. Yes, evil in the form of misunderstanding may occur with the established vocabulary. But then the evil is not in the statement, but rather the misunderstanding. In the one, evil is the necessary attendant, while in the other it is the accidental occurance. We should be quick to defend the language of our historic confessions and authors, and slow to adopt new language.

[1] Matt. 10:32

[2] 2 Tim. 1:13

[3] Woods, Theology of the Puritans, p. 6.

[4] Ibid, p. 6-7.

[5] Ibid, p. 7.